At a glance

Object-based learning (OBL) is a student-centered learning approach that uses objects to create a more profound learning experience. These objects can include artworks, artifacts, archival materials, or digital representations of unique objects. Students typically work closely with these objects, which in turn stimulates interest in acquiring and applying knowledge to other contexts both in and out of the classroom.

Who to Contact

Christina Larson: Visiting Assistant Professor, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement

Amanda Valdespino: Instructional Designer, Learning Innovation and Faculty Engagement (LIFE)

Usage scenarios

The following scenarios come from the University of Miami.

To engage her students in Twenty-first-century approaches to object-based learning, Karen Mathews, Associate Professor of Art History, partnered with Academic Technologies on a class project she called “Animating Antiquity” that brought together art and technology. The students conducted traditional research on eight sculptures from Antiquity in the collection of the Lowe Art Museum. They considered the materials and techniques that comprised the sculptures and also proposed potential meanings for each work. Students then worked with staff members from the Lowe Art Museum and from Academic Technologies to produce photogrammetry of the eight objects--photographing each work from 360 degrees, as represented by this News @ The U article. These images then created the 3D virtual forms of the objects on SketchFab.

The students used this visual data to create 3D prints of the sculptures. Art historical research and photogrammetry imaging culminated in the Animating Antiquity website that Dr. Mathews produced with her students. A selection of the 3D prints along with 3D imagery is scheduled to be on display in the antiquities gallery at the Lowe Art Museum for visitors to learn more about the process of 3D printing and this project. Dr. Mathews received funding from the Andrew W. Mellon CREATE Grants Program to cover expenses associated with this project.

Professor Williamson began working with the Lowe Art Museum in the fall semester of 2018 for the first-year course he oversees “Introduction to Innovation in Engineering,” which is now called “Practical Innovation: Polyineering.” This course was part of the Active Learning Initiative that UM’s College of Engineering launched in 2016. To learn more about the overall initiative for the College of Engineering, please visit Transforming 21st Century Engineering Education.

During this course, students work in teams within a problem-solving framework to develop a product by the end of the semester. The course is comprised of first-year Engineering students and first-year Entrepreneur students. These students visit the Lowe Art Museum for two different object-based experiences. In the first visit, students experience art objects through the methodology of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). As a participant-centered teaching methodology, VTS encourages students to look carefully, think critically, communicate effectively, and listen actively. VTS also offers opportunities to practice team-building skills and self-awareness. Because the “Practical Innovation: Polyineering” course centers on collaboration, these are critical skills for students to practice.

During students’ second visit to the Lowe Art Museum, they explore object-based learning through the lens of materials and methods. Students begin by discussing similarities between visual art, engineering, and entrepreneurship. These include innovation, creativity, marketing, and physical objects. Student teams then go into the galleries, select an object, and study its physical and cultural properties. Students then report their discoveries to the larger group. The entire exercise is rooted in curiosity, discovery, and collaboration.

Recently, Dr. Kate Ramsey offered a new seminar on the topic of “Afro-Caribbean Religion: Healing and Power,” which was also a topic for her book. Her seminar and book project drew upon the research of archival materials in the University of Miami Libraries’ Special Collections and Cuban Heritage Collection. During this course, students had regular visits to both Collections as a class and learned to develop their archival research skills with unique objects and archival materials. In this course, these archival materials served as a link between the present and the historical context of the past.

Each Spring semester, Professor Jennifer Burke has brought her students from the “Voice and Speech Theatre” course to the Lowe Art Museum to engage with the art collection. Students select a work of art that is on display as a source for their own creative response. Although students do not research the art object in an art-historical manner, they instead employ it as a catalyst for developing a monologue that is inspired by the artwork. At the end of the semester, the students perform their monologues before the artwork that inspired them and in front of a public audience.

During the Spring semester, the Lowe Art Museum works with a faculty member and their students from the University of Miami to curate an exhibition as part of the Lowe Art Museum’s annual ArtLab exhibition program. In the Spring semester of 2019, Professor Nathan Timpano and his students curated the exhibition Russia Unframed, which drew on the Lowe Art Museum’s holdings of Russian artwork. The group worked with staff from the Lowe Art Museum throughout this process. They also traveled to New York City and New Jersey to learn more about Russian artwork. They researched the Russian artwork they selected for the exhibition, and they wrote about it for the exhibition catalogue and the digital Guide-by-Cell gallery guide. This curatorial approach to object-based learning taught the students how to conduct art historical research, as well as the logistics of an exhibition process.

References

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College & Conservatory, Teaching with Art in the Science Curriculum, (Oberlin College & Conservatory, Oberlin, Ohio).

- Engaging the Senses: Object-Based Learning in Higher Education. Edited by Helen J. Chatterjee and Leonie Hannan (United Kingdom: Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, 2015).

- German, Senta; Jim Harris. “Agile Objects.” Journal of Museum Education (2017) Vol. 42, No. 3 (248-257). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10598650.2017.1336369

- Miles, Beverly (2018). “Unleashing the Pedagogical Power of Object-based Learning.” https://teche.mq.edu.au/2018/05/unleashing-the-pedagogical-power-of-object-based-learning/

- Romanek, D. & B. Lynch. “Touch and the Value of Object Handling: Final Conclusions for a New Sensory Museology.”’ In In Touch in Museums: Policy and Practice in Object Handling. Edited by H.J. Chatterjee (Oxford & New York, Berg, 2008).

- Tuckett, T., & Lawes, E. (2017). Object literacy at University College London Library Services. Art Libraries Journal, 42 (2), 99-106. doi:10.1017/alj.2017.13. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/art-libraries-journal/article/object-literacy-at-university-college-london-library-services/80551C8D6B24B0E428BF045B4EF960FD

- “What is Object-based Inquiry?” https://us.corwin.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/7139_alvarado_ch_1.pdf

Research Team

Christina Larson: Visiting Assistant Professor, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Academic Engagement

Amanda Valdespino: Instructional Designer, Academic Technologies

Where to go From Here

If you are interested in learning more about object-based learning and/or how to integrate this teaching method into your classroom, connect with the following UM sources:

What is it?

Object-based learning (OBL) is a form of active learning that uses artworks, artifacts, archival materials, or digital representations of unique objects to inspire close observation and deep critical thinking. Wonder, awe, curiosity, and engagement are central to this approach. Unique or rare objects serve as testaments of creativity, evoking a connection between the past and the present. It is a powerful idea for students to realize that as they examine the object, they are standing in the same proximity as the person who created it. This connection can inspire curiosity among learners, which influences how they use discovery as a learning tool. OBL is not limited to the Humanities; it can be employed by many academic disciplines in creative, engaging ways.

Object-based learning holds the object at the center of the learning experience. Objects are sometimes also referred to as primary sources, cultural resources, or material culture. Overall, this type of engagement involves experiential learning and multi-sensory interaction. Learners may focus on learning about those who created the object, the materials used to make the object, its socio-cultural significance, its various interpretations, the context in which it was produced, its current context within a collection, how it is a catalyst for discussion, or how it inspires contemporary creativity. The most common venues for OBL are galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM), but OBL can take place in the classroom as well.

How does it work?

Here are a few steps to consider when incorporating object-based learning into the curriculum:

- Assess learning outcomes and goals: What core concepts do you want your students to conceptualize? What tasks (problem-solving, peer-to-peer interaction, abstract thinking, etc.) do you want your students to experience in order to engage in a deeper sense of learning?

- Select suitable object(s): Which object(s) would be most effective in accomplishing your goals for the class? It is important that the objects are intriguing for your class as they will become the central focus for students to construct knowledge and meaning. When selecting objects, ask yourself:

- Is it complex or puzzling to demand engagement?

- How has it been damaged or de-contextualized?

- How has it been re-contextualized in regards to where it is located and how it is organized?

- Gain access: How and where will students access the object? This step might involve procuring the object yourself, students bringing in the object to class from home, or working with resources such as a museum or library special collections to visit. If your OBL involves the latter, it is crucial to coordinate with appropriate staff in terms of setting up schedules and discussing your classroom needs.

- Consider methods for engagement: How will your students interact with the object? OBL encourages students to learn through close observations, tactile experiences, and inquiry. This can take on various approaches including but not limited to small group projects, creative expression, visual-thinking strategies, technology (3-D printing, AR/VR), or simply leading a classroom discussion with open-ended questions.

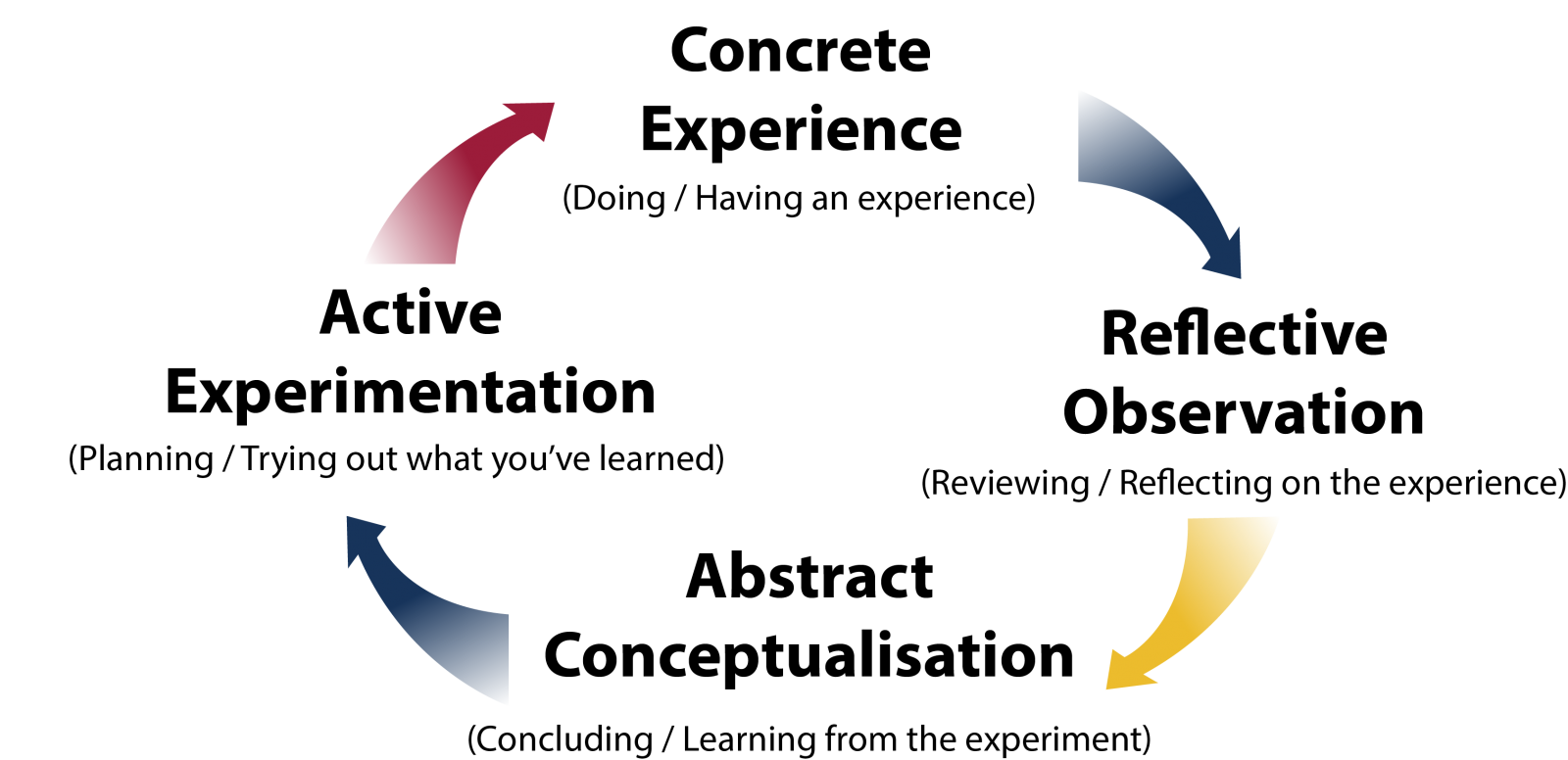

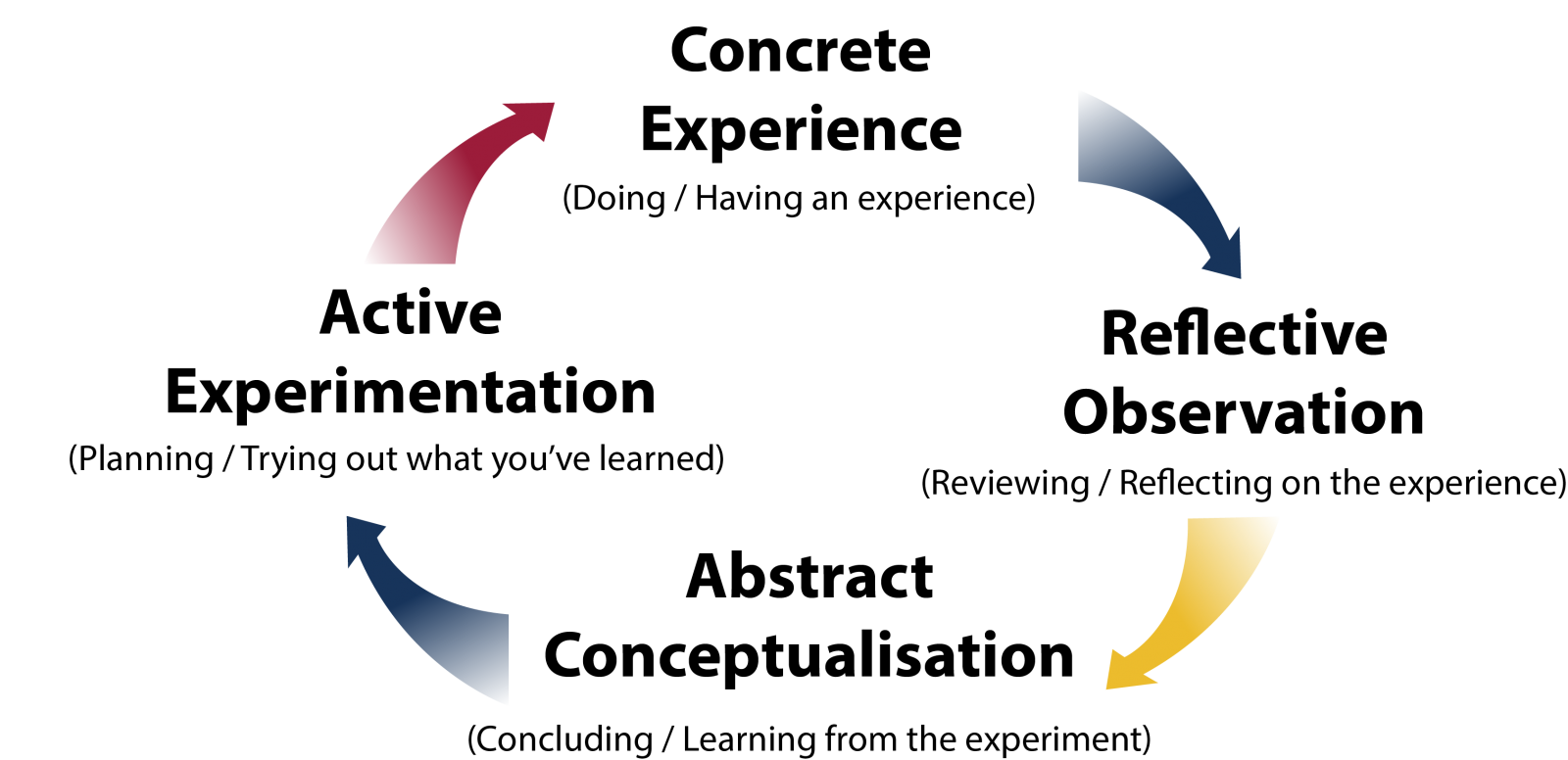

One theoretical framework to examine when thinking about student engagement in object-based learning is Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (Chatterjee & Hannan, 2015). In order for a student to gain any real knowledge, they must participate in, reflect on, and analyze an experience to then learn and actively apply the new knowledge gained to the world around them, resulting in newer experiences. Depending on the situation or environment that OBL takes place in, students may enter this process at any point, but it is crucial they apply all four modes for a more impactful learning experience to occur.

Who’s doing it?

Libraries, archives, and museums are at the forefront of exploring and partnering with institutions on object-based learning. Here are a few examples:

Object-based learning initiative at Penn State: In collaboration with Penn and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Penn State uses object-based learning to provide History of Art graduate students to study art through multiple methodologies. This initiative is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and also included graduate workshops, seminars, and research fellowships related to OBL.

University College of London: This university has been a pioneer in research and implementation of object-based learning. OBL is integrated at the undergraduate and postgraduate level across a variety of disciplines. In 2012, UCL started to offer an “Arts and Science (BASc) degree” that includes a second-year unit dedicated to OBL through engagement with the university’s museums and library special collections.

Professor Virginia Reinburg- Boston College: For the Fall 2014 semester, Professor Reinburg modified her, “Early Printed Books: History and Craft” course by including books from the John J. Burns Library of Rare Books and Special Collections, and having students participate in hands-on workshops at the conservation lab. The students were able to experiment with tools and produce works that culminated at an end of semester exhibit at the library.

Why is it significant?

Benefits of Object-based Learning (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College)

- Nurtures an appreciation for cultural differences.

- Enhances observation skills.

- Cultivates focused attention through slow looking.

- Fosters communication skills and teamwork.

- Promotes dialogue and collaboration among students.

- Encourages creative problem-solving.

- Creates respect for different points of view.

- Builds connections between the academic course and material culture.

- Increases students’ self-awareness as learners.

Because OBL involves experiential learning and multi-sensory engagement, learners’ experience with this methodology has the potential to create a powerful learning experience that they might remember long after the end of the semester. Central to OBL is the idea that working with objects mediates and strengthens learning because this interaction has a long-lasting effect and relationship with memory (Romanek & Lynch, 2008; 284).

There are a range of ways to engage with OBL, which offers great flexibility in aligning with pedagogical goals:

- Problem Solving: Students can be prompted to solve problems that are set based on the object. What is this object? What materials or techniques were used to create it? Who created the object? Which context does the object come from? What is its function? This activity should be mentally and physically stimulating through problem-solving and/or experimentation.

- Questioning: Objects can be used to encourage students to develop their own questions of inquiry. Students can also learn to develop strategies for answering those questions. Students can also use the object to compare with other objects.

- Peer-to-peer interaction: Objects can be used as a focal point and a catalyst for conversation. This type of OBL lesson should feature objects while allowing students to work cooperatively, share their learning with peers, and build their knowledge by learning from others.

- Abstract Thinking: In this scenario, the object lacks connections to real-world applications, but becomes a focus for engagement in learning, especially in a social setting.

- Creative Expression: Objects can also be used to inspire other creative endeavors, from developing new artistic work in visual art, music, writing, or dance--to thinking about innovation and creativity in other endeavors.

What are the downsides?

- Time: In order to include object-based learning in the curriculum, instructors need to allot a large amount of time in planning and execution. As previously mentioned, faculty that need or wish to involve other staff from museums or libraries need to also consider them in their timeline as well as keep in mind their availability and operational hours.

- Logistics: when creating ideal environments for OBL, instructors and institutions can come across issues such as limited storage for artifacts/archives, lack of accessibility to these objects, and lack of space to accommodate this kind of learning, especially if teaching a large class.

- Economics: Cuts in funding can impact OBL by restricting teaching campus facilities conducive to this method, reducing operational hours of libraries, archives, and museums, and having classes taught at a higher student-teacher ratio that would make OBL more challenging to integrate.

- Cultural: Instructors who are experts in their field, but receive little to no teacher training may find it uncomfortable to include other standards of teaching practices or styles.

- Preservation: Museums, archives, and libraries have a responsibility to educate, but also to preserve. Trying to uphold these responsibilities can cause tension when trying to introduce OBL since staff has to consider whether collections should be available for student engagement, or protected to maintain their current forms and prevent any damage or alterations.

- Evaluation and assessment: Although many studies agree there is pedagogical value to OBL, it is often difficult to develop assessment metrics that accurately measure the impact of the experience on learners.

Where is it going?

OBL and technology: Object-based learning has traditionally featured objects within the context of GLAMs (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), but through technology and an expanding definition of what an object is, OBL is moving in new directions. Through photogrammetry technology and 3D printing, students can now study sculptures in the round. The digital 3D versions of sculptures allow viewers to see all sides of a sculpture that are not visible in the gallery. Preservation practices typically do not allow visitors to touch works of art, but a 3D printed version does permit this, which offers additional options for people with visual impairment to engage with sculptures.

Additionally, digitization of archival and other 2D materials aids in the preservation of these materials while making them available to a wider audience. Many museums are moving toward open-access to digital images of their collection materials. Faculty members and students can access these materials more readily than they could even five years ago. OBL has begun including all material culture items as objects to examine. Rather than simply focusing on unique and handmade objects, OBL can include any materials that are made by humans (even those that are mass-produced). In this case, it is the process of engaging with these objects is more important than how they were made.

OBL and assessment: Researchers have begun developing studies to measure the impact of OBL. This work is being executed by library, archival, and museum professionals alike. Although it is not easy to measure short-term or long-term impact on students as the result of an OBL experience, these researchers have begun framing the questions that should enable others to conduct similar studies.

What are the implications for teaching and learning?

- Teachers as facilitators: Object-based learning requires students to take charge and build knowledge either individually or collaboratively as a class. To achieve this, students must critically engage with primary or secondary sources in order to understand past perspectives and how they relate to the classroom. Instructors, although heavily involved in the planning of OBL, must take a step back during the experience process and allow students more control. Guidance is still provided whether through questioning or class assignment instructions, but students ultimately must discover on their own in order to construct meaning when interacting with objects.

- Relation to research: Object-based learning can provide the opportunity for faculty to approach their research or areas of expertise with a fresh perspective. Though students are the focus, instructors also benefit connecting with materials in relation to their discipline. OBL also offers the opportunity for faculty to discuss their research to students in a way that is special and can open doors to more thoughtful conversations.

- Unique access & cultural value: Through object-based learning, students have the possibility to view up close or even touch rare artifacts, artworks, and archives that others might not be able to. These moments afford students access to objects often only available to certain professionals in libraries or museums. Professionals in these settings are typically the ones who decide what to collect and continue to care for. However, by including students in such spaces and giving them experiences through OBL that are uniquely valuable, they can also contribute to the conversation of what materials carry what cultural values.